In Support of Game Jams (pt. 1)

Game jams encourage creativity and learning. This post explores all the benefits of game jams, as well as a history of the jams I have personally entered.

For those who aren’t in the game development community, the phrase “game jam” might not mean much to you, but for me, it never fails to pique my interest. A game jam is a short-term “challenge” wherein everyone participating operates under a predefined, relatively restrictive, time limit in order to create a game-like-product, all surrounding the general theme of the jam. They are highly motivating events that I like to use to try out / learn something new, and very much encourage people to take place in any that pop up that might interest you.

Now, there is a fairly pervasive opinion that doing jams is a “waste of time” because completing them distracts from your main project. They have valid points — you’re using time and energy you could be devoting to your main game to little side games that often don’t go anywhere, or if they do, then take up even more time and energy away from your main project. And while there are certainly times wherein this is something I consider, I often find this line of reasoning to be faulty.

Because here’s the thing — first, that assumes that everyone even has a main project to begin with, which I have learned is not always the case. There are many devs who love making games, but much prefer to focus their energies on these smaller, more insulated, types of projects. And downplaying their preference also downplays their place within the indie dev space unfairly. They, however, might not necessarily be the person who this sort of argument would be best used on. But, even for someone like me who does have a main project, I would argue that time spent away from it, while still working on related skills, is not a waste of time for said main project. Sure, the time is not directly being applied to the game file or elements of All the King’s Men (my main project, which you can wishlist HERE), but as I’m working on these jam projects, I’m still working on and refining the skills that I will be using in the main project. That kind of growth is transferrable; it doesn’t just disappear because I learned things and improved while working on a jam game instead — sometimes years before I would have had to learn them for my main project. This only serves as a benefit because now, I can go into some of the end-stages of All the King’s Men with forethought, skills, and abilities that I would not have otherwise had regarding release, player reception, and post-release.

In addition to building this transferable knowledge, I find game jams allow me to be much more adventurous. Since this is “just a jam,” I often try complex mechanics or systems within my game to give them a bit of a “trial run” before considering how they might be applied to something like All the King’s Men. If I try it out in the jam game and everyone hates it, or doesn’t understand it, or it absolutely wrecks the pacing of the game, I know not to include it in the main project — or I have ways to fix the problems ahead of time, prior to the release of something I’ve spent years upon years working on. With less pressure to make a perfect version of something, there is much more flexibility with the process — and far more forgiveness by the players.

Finally, calling a game jam a “waste of time” implies that the jam game itself isn’t meant to be developed into a viable project. Now, that’s not to say that ALL jam games are meant to take themselves seriously and become magical works of art, but this idea that you’re “wasting time” by participating in them does regularly lend to that belief. Personally, I think that any game made for a game jam is perfectly able to be fleshed out to be just as legitimate of a game as any so-called main project would be, and I think you’ll find evidence of that as I elaborate a little about the game jams I’ve participated in a little later in this article.

All of those points, while logical, don’t negate the fact that there are people who refuse to play games made during jams because they’re “just a jam game.” I think that’s a mentality that needs to be reconsidered. If the theme of the jam was to make meme games (or horror, or platformers, or insert any specific preference here) and that’s not something you personally want to engage with, that’s perfectly valid. But to completely write off a game simply because it was made — or at least started — as a part of a community event like this? I think that is outright silly. Games like DELUGE, Baba is You, Celeste, OneShot, and Inscryption were all originally jam games (among several others). Does that make them any less “real” of a game? Does that make them a “waste of time” or a “distraction” from those devs’ “real projects?” Absolutely not. Realistically, are breakout, hugely successful games like that more of an exception than a rule? Of course. But if people had written them off as “just a jam game,” think of all of the amazing things the video game industry would be missing out on.

I mentioned that I do recognize that there is some legitimacy to the argument, as well, however. And that is the fact that sometimes, in order to make these jam games into a legitimate, viable product, you do have to devote (much) more time than just the jam into them, which could potentially delay the development cycle of your so-called main project. If there are looming deadlines, this can absolutely become a real issue. But if said deadline can be moved — or don’t exist at all — I think that being flexible with the “main project” to allow these smaller projects to temporarily become your main project isn’t a terrible idea in the grand scheme of things. Not only for the reasons and benefits outlined above, but also to help build a player base and for marketing purposes. I could talk ad nauseum about the importance of this particular aspect, but I’ll spare you all that essay (at least for now), and instead, tell you a little bit about the game jams that I’ve participated in over the years.

My Game Jam History

The first game jam I ever took part in was the “No Words” game jam hosted by Vagabond Dog. The name of the jam gives you a pretty clear idea of the theme of this one — to make a game in seven days that contains zero words. This isn’t just in the game play, but also the menus, tutorials, title screen… everything. For this jam, I made a game called “Trick or Treat,” wherein you chose one of three costumes to dress up as to go through a haunted house, slay some monsters (using an active time battle system), and bring back enough treats to personally enjoy.

I remember being incredibly nervous going into this jam, but also so very excited. I was an active member of the Vagabond Dog community at the time, since he streamed game dev on his game Sometimes Always Monsters during the work day, and I could always pop in while I was working through my afternoon tasks, so being able to participate in an event within the community that I was enjoying so much meant a lot to me. But, I was also very nervous because outside of a few very small, very basic games that I made with / for my brother, and the (at that stage) very little amount of work I had made on All the King’s Men at that point, my dev experience was VERY minimal.

So, in addition to being a little baby dev, I also had never done something like this in such a restrictive time frame, either. I did my best to scope small and set appropriate expectations, but, well, best laid plans and all… While I wouldn’t say my initial plan for the game was overscoped, but as I kept working on it, the plan began to spiral a little bit out of control, at least for a week-long project I was completing on my own. Because of that, I absolutely experienced my first and only real period of crunch the final 24-36 hours of the jam. To finish the game in a state that would make sense for a demo, without words, and also do the best testing I could before it was to be played on stream, I ended up staying up the entire crunch period and doing absolutely nothing but dev for that time. It was a lot and I vowed never to put myself through that kind of stress EVER again. Something else that had my nerves on-edge for this event was the fact that this would be the first time anyone had ever played a game I made — outside of my brother, of course — and this would be played live on stream, for a decently sizeable audience. In the end, people really seemed to enjoy what I’d done, and I learned so much technically, but also about timing / deadlines, scoping, and started getting used to watching something I’ve made out in the wild.

As for the future of this game, I do plan to finish it up by adding in the remainder of the extra content (three more costumes / routes to collect the treats in the haunted house, a haunted corn maze, and a third ~secret level), and add in some actual words, now that the jam restrictions are no longer needed, and releasing it in full on Steam for $0.99.

The second jam I participated in was another hosted by Vagabond Dog for the “Moving” jam. As with the previous one, the title pretty well explains the theme: it had to somehow incorporate the idea of moving or traveling. I can’t completely remember if this was a shorter, three-day jam, officially, or if I only had the weekend available to work on it, but I do remember only spending a few short days on this game… and it showed. But, despite the very unfinished state of the game, I still submitted it to be played and it was, in fact, playable to completion, so I count that as a success.

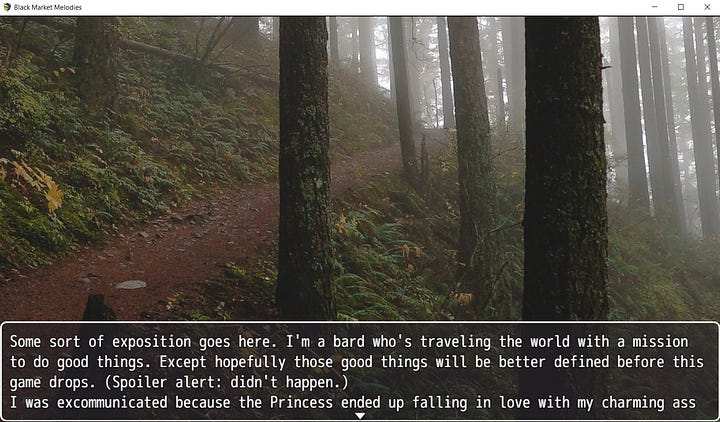

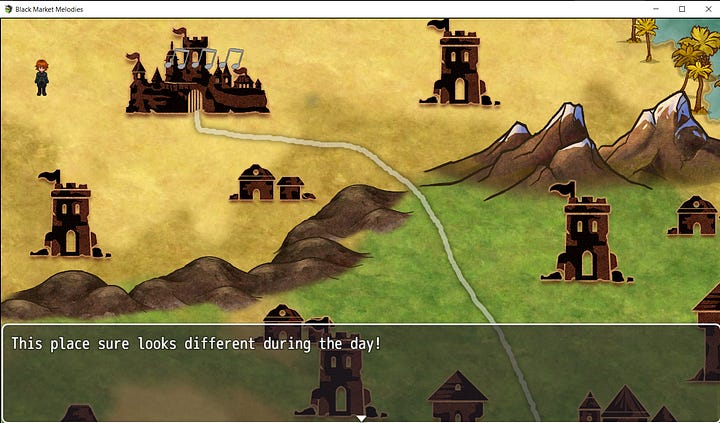

I made a game called “Black Market Melodies” and I honestly don’t fully remember the narrative of this game (it was something about a bard who’d been excommunicated? but that’s all I’ve got), but I do remember that I was trying out a writing style that was a little unexpected coming from me (it was very snarky and funny, and caught a lot of people off-guard), and it landed exactly in the way I wanted it to. There were a few other things that I was really focused on trying out with this game: using a rhythm game as a battle system and using a parallaxed image of a map as the method of “moving” throughout the game. While the battle system wasn’t perfectly timed, I managed to manipulate things as best I could to make it playable, so I was happy with the work I put in on that one. The map, however, worked flawlessly and people were equally impressed by that as they were by the writing.

This game jam was really instrumental in boosting my confidence sharing my games. Because even despite it not being perfect, or finished, or even a sliver of the expectation I had for it, I still shared it, and people still found a lot they enjoyed about it. Despite that, I don’t really have plans for this game at all, outside of hosting it here for my paid members to try out, if they so desire.

The third game jam I participated in has resulted in my most popular jam game yet — Elmo’s Pub Crawl — as a part of the RPG Maker 2k3 Jam hosted by Riggy2k3. The theme of this jam was to make a game over the course of a week using the specific RPG Maker 2k3 version of the engine. While there are a lot of similarities between the 2k3 engine and RPG Maker MV (which is the version of the engine that I use), there are also a lot of differences in what the engine does, how it does things, and even down to the kinds of files it uses and the format the colors have to be in. Thankfully, Riggy was a fantastic host and he provided plenty of resources and guidance to get all of us through the jam successfully, but learning the ins-and-outs of what felt almost like a brand new engine was by far the most difficult and challenging part of this jam.

That being said, I am quite thankful that I did learn this particular version of the engine. Because of that legitimate limitations and restrictions of RM2k3, I was forced to think about how mechanics function at the most basic level and figure out a way to apply the knowledge I already had to make everything work how I wanted. I really learned how to structure an event to be “most” optimal, and the most streamlined that I possibly could. With all of the bells and whistles stripped from the engine, the focus was shifted to the bare bones functionality, which helped as I dove into much more complex events in All the King’s Men. While I don’t think I will ever voluntarily make a game in this engine ever again, it’s the RM version of learning to walk before you can run.

There was a lot of creative liberty allowed in this jam — the description on the jam page even states that “participants are encouraged to fuck around and find out.” So I decided to do just that and make a meme game of sorts based on a comedy skit from another online community that I am a part of. Because of that, I faced the second largest challenge of this particular jam: making a game for two very different communities, with in-jokes from both of them, while still being valid, understandable, and funny for both. While I do think I accomplished that, there are things that I would like to lean more into and do even better in future iterations of this game. Which… I do plan on having. Like I mentioned, there’s a few places where I want to go a little harder on the in jokes for both communities, there’s one “puzzle” that thematically doesn’t make any sense that I’d like to figure out a way to make a little more appropriate to the game itself. There’s one scene that I very much half-assed the scene to finish the game in time, one more silly scene that I had envisioned for the game that I’d still like to add, and — as these things always go — there are a few buggy bits that I still need to iron out (not to mention the new ones that I’m sure will be introduced by the addition of the new content). But, outside of those fixes, I don’t intend to do anything else with this game whatsoever, and if I never find the time to do those things? I consider this game complete. Plus, I don’t know that I’ll ever get another comment to rival this one:

As this game is fully released, if you are interested in giving it (in its current, unfinished and slightly buggy version) a try, you are welcome to download it on its itch.io page. The instructions for how to install and play the game can be found in the Read Me once it is unzipped, since 2k3 games need a little bit of love before they can be played.

From here, I had a very unfortunate event that absolutely gutted me, and resulted in my first ever game jam that I entered… and never shared my project for. This was for RiggyJam 2: the “C.I.” Game Jam (C.I. = copyright infringement). Now, despite my current biggest claim-to-fame being a “fan game” that definitely could be considered a meme game, that genre is really not my thing. So for this one, I considered a few possibilities — making a Super Mario RPG 2 (ruled that out due to being insanely out of scope, even if I would have set the goal of only completing up through the first mini-boss / first area), a FFXII spin-off / demake about Basch’s time before joining up with the party OR an AU where Reks had a happier ending, and a second game for the same community that Elmo’s was for: Snale Fantasy (misspelling intentional, but this was also ruled out because it would’ve been too big of a project for a week). There were a lot of ideas, all of which I might eventually still consider exploring, but ultimately decided that I wanted to make a DZ & Riggy community-based “demake” of the classic, underrated NES RPG “Crystalis.”

Because this isn’t a game like Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest, the tiles were often not something anyone else had already ripped / compiled, so I spent a large part of my week working on that. While this wasn’t necessarily anything I didn’t know how to do, figuring out how to pull something from a game that was definitely originally made with 16x16 tiles and put it into the 48x48 format cleanly and still being representative of the original game was… quite a task. It was mostly time consuming, however, rather than difficult — once I figured out how to do it initially, that is.

Outside of that, I spent a lot of time in an external document writing and figuring out how I was going to transform the original story into one about the DZ & Riggy community, which characters from the original game would represent the members of the community and why. This took another large chunk of time, but it was the first time I’d ever bothered to put together an actual, organized game design document (GDD) like this, and oh man, did that change my life. After this jam, I started creating a GDD for All the King’s Men so I wouldn’t have to rely on my memory for all the details and information about the game, or keep track of all the millions of pieces of paper that I was jotting things down on at the time. This has not only streamlined my development process, but it has also saved me so much stress over things I inevitably would have forgotten.

By demaking a game that was so functionally limited by the hardware of the time, I also spent a lot of time examining the level design of the game, and the ways in which it telegraphed the player’s next goals to the player — spoiler: it wasn’t very clearly done — as well as ways that I could improve upon that for my players’ experience. It taught me a lot about iterative levels, linking areas, and ways to deal with players visiting and revisiting certain areas (as well as several things to avoid).

Unfortunately, late in the afternoon of day five of this jam, as I was working on the game — I was putting the final touches on the first dungeon and testing the first official boss — tragedy struck in the form of a common Florida thunderstorm. However, this storm did the unthinkable and knocked my power out while the engine was open, fully corrupting the entire project. For the next 12-18 hours, myself and three other much more tech-savvy friends and I did everything we could to try and recover the game, but it was to no avail; the game was gone. The only thing that remained were the screenshots I had shared during the creation process…

… and the GDD with all the stats, text, and mechanics meticulously written out!

While I didn’t have a chance — or the heart — to recreate everything I’d spent the last five days working on, because of my decision to make a GDD for this particular project, a lot of the guts of the project does still exist, living in a document, waiting. Waiting for the day that I return to it and create the community game that never was and always will be (which, eventually, I do intend to do). If you’d like to check out the premise of the game, as well as the few remaining screenshots, you’re welcome to do so at the game’s itch.io page.

From this point, I took part in the longest — and I would argue my most successful — jam yet: the 2022 iteration of the Indie Game Maker Contest (IGMC). However, I’m going to hold off talking about that experience, as well as my nonexperience with this year’s RPG MAKER 2025 JAM, and RiggyJam 7 for my post next week, where I’ll be diving into the importance of community and… behavior(??) in events like this.

But before ending this post, since even the one “loss” of these have all been wins… I’d like for you to know that after IGMC, I entered, and failed to submit a project for two additional RiggyJams — RiggyJam 3: “Dependable Friend” and RiggyJam6 “Spooky Surprises.” For both of those jams, I had ideas and started projects, but petered out before getting anything I even considered worthwhile to submit. Amusingly enough, I completely forgot that I had even started a project for the “Dependable Friend” jam until I started compiling my list of projects for this post. Not being able to take place in the “Spooky Surprises” jam really bummed me out because I had a super cool idea that I wanted to do and share, but the jam happened to fall during one of my busiest weeks at work, and I simply couldn’t devote the time (or brain power) to making a game — even at the alpha / tech demo level — that I would be proud of. That one, however, will eventually see the light of day in some form or another!

Have you ever taken part in a friendly competition of this sort? What are your thoughts on participating in game jams?

Want to read even more about my history in game jams and how they impact the community at large? Continue on to part two:

Game Development Community: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Game Jams, pt. 2)

Last week, I talked a little bit about what Game Jams are and why I don’t consider them a “waste of time” or a “distraction” from a main project, as well as several of the smaller, traditional Game J…