Game Development Community: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Game Jams, pt. 2)

The second part of one solo dev's deep-dive into game jams, this time focusing on the positives and negatives regarding community building.

Last week, I talked a little bit about what Game Jams are and why I don’t consider them a “waste of time” or a “distraction” from a main project, as well as several of the smaller, traditional Game Jams that I’ve taken part in. This week, I want to examine the ways in which Game Jams foster — or prohibit — community, the importance of that, and what it means to be a part of that community (not just personally, but also looking at the behavior of participants throughout the events).

I, personally, much prefer the smaller community-based jams — that’s why I’ve done so many of the jams that Vagabond Dog and Riggy have hosted. They give you an opportunity to get to know the other participants and their projects, as well as offer / ask for help without feeling like you’re shouting into a void of people who are too involved with their own work to spend a few minutes interacting with someone else who’s in the weeds alongside them. But to talk about jams without also looking at the “big” ones with 100+ entries and cash prizes on the line would be a complete misrepresentation of game jams as a whole.

I, admittedly, haven’t participated in many of these — only one, fully — though I have also been a participating community member for another, and a forced-into-being-a-spectator for another, so they aren’t unfamiliar to me.

My Experience with Large Jams

The first of these I’d like to highlight is the RPG Maker MZ Touch the Stars Game Jam. I did not submit an entry to this jam. At the time, I was not confident enough in my skills to put a game together that would be “worth” submitting to an event with a monetary prize pool attached for one. I also thought I would be at a pretty heavy disadvantage from the start, because I missed the start of the jam / didn’t realize it was happening until about halfway into the development period. So, I decided to skip this one, but to keep an eye on it regardless. Because of that plan, I did play between 45-50 of the approximately 100 entries and rate them before the judging period was up. This was my first real exposure to a jam of this scale, and I had so much fun watching streams of other people playing the games, talking about them with the creators / other devs, and feeling like I was still a part of the process by rating and offering them feedback. While there were a few people who were consistently tearing down every single game, and only pointing out the flaws, they (and their communities) were easy enough to avoid, leaving the overall experience to be positive and encouraging. Plus, with the large range of skills and abilities that were presented by the games that had been entered, I knew that while I probably wouldn’t win, I also wouldn’t have the worst game entered, either. And as much as that really shouldn’t matter — the only person you’re ever really competing with in these situations should be yourself — it was the confidence boost I needed.

So after the positive experience and that realization that maybe I’m not the worst dev on the planet, I kept an ear to the ground for the next large jam, resolved to join it. When it came around, I also managed to convince a few friends to do so too, because stressing yourself out for a month to perfect a game is always better with friends… right?

This jam was the next Indie Game Makers Contest (IGMC), which is a game jam that happened semi-regularly, and offered quite the prize pool (1st place would be taking home $10,000), and pretty wide recognition throughout the community. The theme of this one was Rebirth, Rejuvenation, and Resurrection. Just from reading that, I knew there were going to be a lot of isekai games, a lot of zombies, and a lot of phoenixes. And while my game did nothing to change that fact — involving both phoenixes and zombies (kinda) — I wanted to make sure that even within those common factors, my game was interesting and unique.

I almost immediately had the idea to do a heavily narrative, very moody, puzzle game with a heavy foundational basis in actual science investigating the real world possibility — and repercussions — of resurrection. But, of course, I couldn’t stop there… I had to hit it with a heavy theme, too, just to tie everything together and drive it all home. So it focused a lot on the idea of what it means to be human and the value of a human life. In the latter half of the game (which didn’t make it into the IGMC version, unfortunately, but also would be long after the 1-hour judges’ limit as well), this becomes heavily apparent, and the player experiences firsthand the dangerous side of not respecting life (or death, depending on your perspective, I suppose).

For me, that one-hour judge playtime limit was actually a large part of the challenge of the jam. About halfway through the jam, I realized the game would not be contained within a single hour, and would instead be closer to 5-6 hours, which presented a small problem. I wasn’t willing to rescope the game narrative to fit within an hour, so I had to figure out what point in the narrative would be a good stopping point to (a) keep people interested and invested in playing the full game and (b) give them some closure so it felt like an intentional ending point, not just a situation where “oops, dev ran out of time!” I didn’t want to put them too far in (act 3 / the climax) because I felt like it would be very unfulfilling to stop there, but also didn’t want to stop with just act 1, because that didn’t seem like a full representation of the game, either. Thus, I decided to cap my development for the month at the end of act 2, with a slightly-altered version of the transitional cutscene to give some sort of logical end point / cliffhanger that both the players and I would be happy with.

Now, were there flaws in this method? Yes, absolutely. The dream world that you go into in act 2 isn’t well-explained and doesn’t make a lot of sense without the context that follows in the latter half of the game. Looking back, I definitely could have explained that a little better with another (very quick) cutscene to start off act 2. It also does a pretty bad job of explaining who the playable character for act 2 IS and why you’re switching into her POV in the first place. While it is very quickly explained in the absolute LAST line of this demo version, it doesn’t feel super fluid or cohesive, and I think that hurts the really solid atmosphere that I had worked so hard to establish in act 1. But, overall, I do feel like ending the “demo” there was the correct choice, and with another few days to polish, I probably could’ve tightened those narrative elements up to feel even more complete. Which might seem like a strange wish, considering up until this point, I’d been working on jams within the confines of a single week, and this one was a whole month long. Did I really need more time?

I mean… of course. Every game always needs just a little more time than you expect it too. It’s why deadlines are so frequently missed, and so important to set for yourself. But having a full month to work on the project came with more challenges than advantages in my opinion. First was the temptation to over-scope. With a single week long jam, you’re forced to keep the project small because you’ll never get anywhere close to finishing anything if you don’t. But with a month? That’s four times the stuff you can do! Unfortunately, it also meant that at the beginning of the month, I felt like I had SO much time to do things that I didn’t push as hard as I maybe should’ve, since there was always “tomorrow” to get it done. Except eventually the endless “tomorrows” dwindled down to only being a few days left and those pushed off goals were too much to handle.

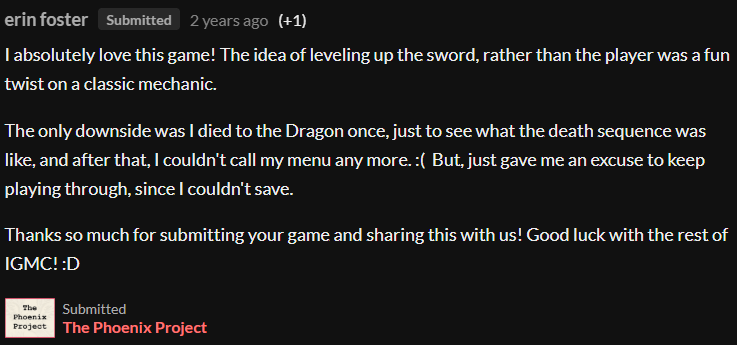

The game I made was called The Phoenix Project (that’s the game page, if you want to check it out for all the details, and also to maybe admire the work I put in on designing the page because I’m quite proud of how good it looks). There’s not a build available for public download at the moment because the state it’s in now is a smidge broken from the work I put in on it post-jam that isn’t fully implemented / polished. Basically, there’s a lot of half-started elements that don’t fully connect into the narrative or the gameplay and just end up accidentally being red herrings at best and game breaking at worst.

But, thankfully, my process in developing this game was the cleanest and most efficient by far, so it’s incredibly easy for me to jump back into my state of mind when I was developing this game originally, even years later. I reused the basic format of the Game Design Document that I had created and started using back for the C.I. Jam, but was even more detailed in the information that I included. This was — I believe — the first time I had actually laid out any form of development calendar, ambitious and vague as it was.

Now, of course, I didn’t stick to that even remotely, but I made one. And it got me in the practice of setting up that sort of general outline of progression for myself for everything moving forward. Even if what I’m working on is something that isn’t necessarily on a deadline like The Phoenix Project was, having this sort of roadmap has really helped me to prioritize tasks and quantify progress, even when said progress isn’t always visible (which is a huge problem with a lot of game development and can often be incredibly demotivating). And honestly? Having that general calendar in place, as time progressed, kept me very aware of how much content I was going to need to cut in order to meet the deadline, since that final week was all nonnegotiable.

When it was all said and done, however, the game was submitted… and I noticed bugs immediately. Which, great, cool. I’m now locked in for an entire month knowing these tiny errors are there, staring me in the face. Thankfully, even despite that, the game was generally well received (outside of people hating puzzles, which was an opinion I didn’t realize was SO widespread), and I was unendingly proud of what I had put out into the world (and since it placed 16/143 for the people’s choice with a rating of 4.152/5, I’d say other people enjoyed it overall as well).

So then… was the judging, which I would argue was at least an equally important aspect of the jam, if not even more important than the development stage. For the next month, people were invited to play the games that had been submitted, rate them, and leave feedback on them. After a few days of casually playing through a few of the entries that had been made by developers I knew and watching streamers playing the games, it became abundantly clear that people really didn’t understand how to give fair and effective feedback or how to behave within an online space. Throughout these first few days, I witnessed so much appalling behavior by developers, players, and judges alike. I’m talking judges bad-mouthing developers, not criticizing / disliking their games, but having public conversations with other judges during a livestream wherein they said multiple developers were “idiots” or “brain damaged” and other things that are genuinely nasty enough that I don’t even feel comfortable reposting them here. Or devs joining livestreams and their first chat being “play my game.” No hello, no please, no nothing. Just demanding. And then they don’t interact with the streamer at all other than about their game, rarely even following them, and just leaving when a streamer said “maybe later” and almost always leaving after they’d seen their game being played — ignoring every other game that had been slaved over by someone else. I even saw one dev who argued with a streamer when they said they’d consider playing that dev’s game after the list they were already planning to play that day. Or streamers who would see small mapping errors and then immediately go off on how horrible a game is, or how much of a waste of time it was that the dev bothered to submit such a terrible game at all. It was honestly kind of shocking to me to see not just so much general negativity and tearing people down, not just games, but also the way that other members of the community either said nothing or joined in.

It bothered me so much that I had multiple conversations with a fellow entrant and good friend about the behaviors we were seeing. He expressed similar concerns, and so we set out to do what we could to improve the overall experience that people were having by committing to playing all 143 entries, rating them, and leaving real constructive feedback for every game. Now, admittedly, I didn’t quite hit every game with all of these pieces, but I did play and rate every single game. There were a few games that I either didn’t get around to writing feedback for, or I just genuinely didn’t have feedback that I could give for a variety of reasons (usually because the game was freaking excellent, and I felt bad just writing “WOW THIS WAS AWESOME!” after leaving paragraphs for other entries).

As the two of us started doing this, we noticed two things:

Other people joined in with us. This was a huge benefit to everyone in the jam. Not only did it get devs in the habit of playing other games and forcing them to practice writing legitimate feedback, it also ensured that all of the games got multiple people with multiple different playstyles testing their game and sharing their thoughts and ideas.

Even people who weren’t playing all of the entries would often return the favor and play / give feedback on games by people who commented on their game. Now while this is, in my opinion, not a great practice to get in (the idea that someone else’s game is only “worth playing” if they have first played your own is very selfish, I think), it still got more devs involved in this very important step of the jam.

Ultimately, both of those things made the entirety of IGMC 2022 feel much more like a community of devs who were (almost) all invested in everyone improving and getting better, not just out for their own game getting played by as many people as possible, begging for 5* ratings, and pretending like the jam was a popularity contest for them to win. And that was cool. Now, did all of the negativity stop? No, of course not. But with some more not-always-negative popping up, it started to drown out the otherwise prevalent voices of the dissenters.

Now, I’m not delusional; I don’t think that we were the only reason this happened. However, comparing the number of comments on every single game page and the number of ratings in this jam with the one I’m going to talk about next… I absolutely think that we had a positive impact on this particular jam. And is why I’m as upset as I am about this year’s large RPG Maker Jam.

Going into this one, I was excited. I had an idea that I thought was going to be fun as hell to work on (you’re playing as an apprentice in an adventurers’ guild who gets left behind by the heroes to do the mundane tasks of the guild — including a handful of fetch quests none of them could be bothered to do — when you stumble into an unexpected, world-threatening mystery that has to be stopped to prevent an ancient prophecy from coming true and ending the world as we know it! Skill growth was going to be linked to growing confidence and the subversion of expectations, the end villain was going to be another unexpected twist (that I won’t spoil because I do still want to make this game at some point), and there were going to be multiple, dynamic endings…). I was also excited because the team of judges for this jam was comprised of 50% friends of mine (+1 semi-acquaintance and 2 strangers) so I knew that the nasty behavior of the judges that I’d been privy to in IGMC wouldn’t be a thing this time, so ultimately it would be a way better experience just out of the gate.

Unfortunately, the time of year the jam took place was the start of one of the busiest times of the school year, especially having just come off my NOLA trip, and I just couldn’t carve out the time to work on adding another project to my plate, let alone one with such a short deadline. I was okay with not being able to submit a game, however, because I knew that when the rating period came around, I would have MUCH more free time, so I could, once again, set a goal to play, rate, and give feedback on every single entry.

Imagine my disappointment when I opened the submission page, bright and early the morning after the jam ended to find that I was blocked from rating because I didn’t submit an entry. And that disappointment only deepened when I found out it was an intentional choice because they didn’t want it to become “a popularity contest.” Except, it still did… just now, it was only between the people who had the chance to enter, not the whole community. And, since there was a panel of judges who would be creating the winner’s list, it really didn’t matter at all if it ended up being a popularity contest at all. But instead of “risking” that, the head of the jam decided to turn it into a good ol’ devs’ club and tell the rest of the community “well, you can still leave comments, even if they don’t count for anything or impact anything at all because you’re not good enough to be a part of this!” (Okay, so they didn’t say that last part, but for those of us who were now blacklisted from participating in the community-focused aspect of the jam, that sentiment was very much implied.)

And so, I didn’t get to take part in the most important part of game jams: the networking and community building aspect. All because I happened to not want to submit a subpar, rushed, piece of garbage out of respect for the judges, their time, and my own “reputation” within the community. And that was bullshit, to be frank.

And here’s the funny part… While I mentioned above that I’m not delusional and I don’t think my friend and I were the only thing that impacted the outcome of the 2022 IGMC comments / ratings / feedback, the numbers do show that maybe blocking active members of the community from interacting with the jam is a bad idea.

For IGMC, there were 143 entries and 2,180 ratings — which is approximately 15 ratings per game. And if you flip through the submissions, I don’t see a single game with less than 5 comments on their submission page. Some have upwards of 20 comments (all of this excluding the comments from the judges). There was so much interaction with every. single. submission. For the 2025 jam there 261 entries and 892 ratings which is less than 3.5 ratings per game. Most submission pages are lucky to see 2-3 comments that aren’t from the judges directly. You can’t tell me that the threat of entrants maybe asking a few non-dev friends to come skew their ratings a little bit was worth the drop in interaction and community building. There were almost double the entries… and five times fewer interactions. That is absurd.

And that’s not to mention the streaming changes. Audiences were not tuning in for many of the showcase streams from the judges. Several RM streamers who would normally stream entries stopped one or two streams into playing them, if they even started / played any games at all. And — though I’ve said it before, I think it’s worth repeating — it is incredibly disappointing to see this very community-focused part of the game jam being destroyed. It’s almost like when you make part of your community feel like they’re not as important as the rest of the community… they won’t pay any attention once you’ve alienated them and cast them aside as “less than.”

Substack tells me that I’m nearing my email limit for this post, so I’ll throw my final thoughts on game jams, as well as talk about a less-than-traditional jam I participated in this year that did community correctly in my post next week. I’ll share the jam archive page for paid subscriptions in that post as well.

Thanks always for reading; see you next Monday for the thrilling conclusion to this series on game jams.

Game Jams: Final Thoughts and Doing them "Right"

I would like to start out with a little bit of a disclaimer here. Like with most things, correctness (in this sense) is all a matter of subjectivity and personal taste; what might make a Game Jam “ri…

Sounds a lot like how the "real" world works. Those in charge do not want to change or hear opposing voices, ideas, or be critzied. Sad.

The PP's page is so cute. SO cute.